Articles

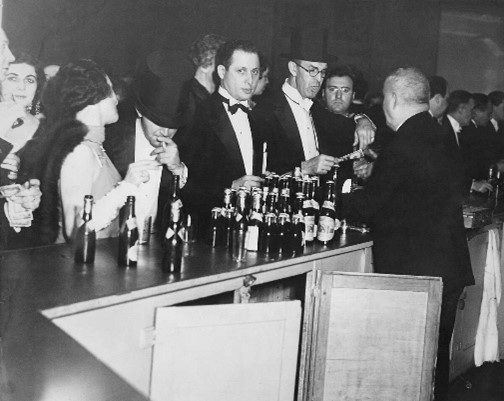

Prohibition in San Francisco

San Francisco voted overwhelming against Prohibition. In fact, while Los Angeles voted to go dry, the vote in San Francisco was 83% to stay wet. At the time, San Francisco consumed more alcohol per capita than any other city in America. The city’s population favored “pleasant living” and that included a drink or two. Many of San Francisco’s citizens felt that you just couldn’t legislate morality.

The start of Prohibition brought big changes across the country and the Bay Area, but in San Francisco Prohibition was not much more than a rumor. As a port city, San Francisco was pretty much wide open during the Noble Experiment’s 13 years.

Not long after America went dry, the Democratic National Convention came to San Francisco. Mayor James Rolph enlisted a group of society ladies who, wearing white dresses, delivered a bottle of bourbon to each delegate. The gift was given with “the complements of the City and County of San Francisco”.

Enforcement of the Volstead Act (which enabled Prohibition) was so lax that Shanty Malone’s Bistro on Turk Street would stage phony police raids to amuse the customers. Across the Bay in Oakland, the Alameda County District Attorney Earl Warren tried to enforce Prohibition.

Supplies of liquor from Canada were brought ashore from ships anchored off the San Mateo, Sonoma or Marin County coasts. Booze coming in from Marin or Sonoma was trucked to Sausalito to be loaded onto ferryboats. The mayor of Sausalito helped smuggle booze into the San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood.

As Treasury agents obtained faster boats the rumrunners found new and secluded landing spots for their “imported” liquor. Some favorites were Paradise Cove in Marin County and Pescadero, Princeton-by-the-Sea and Moss Beach south of the city along the San Mateo coast. In 1927, today’s Moss Beach Distillery opened as Frank’s Place. This speakeasy was never raided and was popular with many prominent members of San Francisco society including Dashiell Hammett.

Ships from Vancouver carrying Canadian whiskey would anchor in Half Moon Bay and their cargo was transferred to fast boats, faster than those used by the Revenue Agents. Once they even used a submarine to smuggle the liquor ashore.

No “mob” or organized crime cartel ever fully developed in San Francisco to control the illegal liquor trade. The reason was simple; the police had no desire to enforce Prohibition and besides they wanted the business for themselves. In San Francisco, Irish Americans dominated the police and the courts. In a city with a high percentage of foreign-born residents, the citizens drank and supported drinking. The Board of Supervisors even passed a resolution telling the police not to enforce the Volstead Act.

In 1922, San Francisco Police Chief Daniel O’Brien oversaw the operation of 1,492 speakeasies. Saloons, hotels and restaurants who served liquor made payments to the police “widow and orphans fund”. The District Attorney avoided charging bootleggers. In one of San Francisco’s more famous bootlegger trials, the jury drank the evidence and found the defendant not guilty.

In Italian North Beach, Sicilians tried to control the neighbor liquor trade. The police shut down any up-and-coming Italian mobsters and maintained control.

San Francisco found creative ways to supply thirsty citizens. At the Palace Hotel, if you ordered flowers with dinner a bottle of whiskey came in the box along with the bouquet.

The St. Francis Hotel even built a secret floor for liquor storage and a speakeasy in the basement. A secret tunnel connected a popular watering hole, The House of Shields with the Palace Hotel running under New Montgomery Street.

Prohibition changed social practices by making it fashionable for women to join men in social outings. The Irish and Germans wanted beer, the Italians wanted wine and everyone else favored gin, whiskey, and bourbon.

Toward the end of Prohibition, in 1933, there were an estimated 6,000 speakeasys in San Francisco.